Why is rheology important?

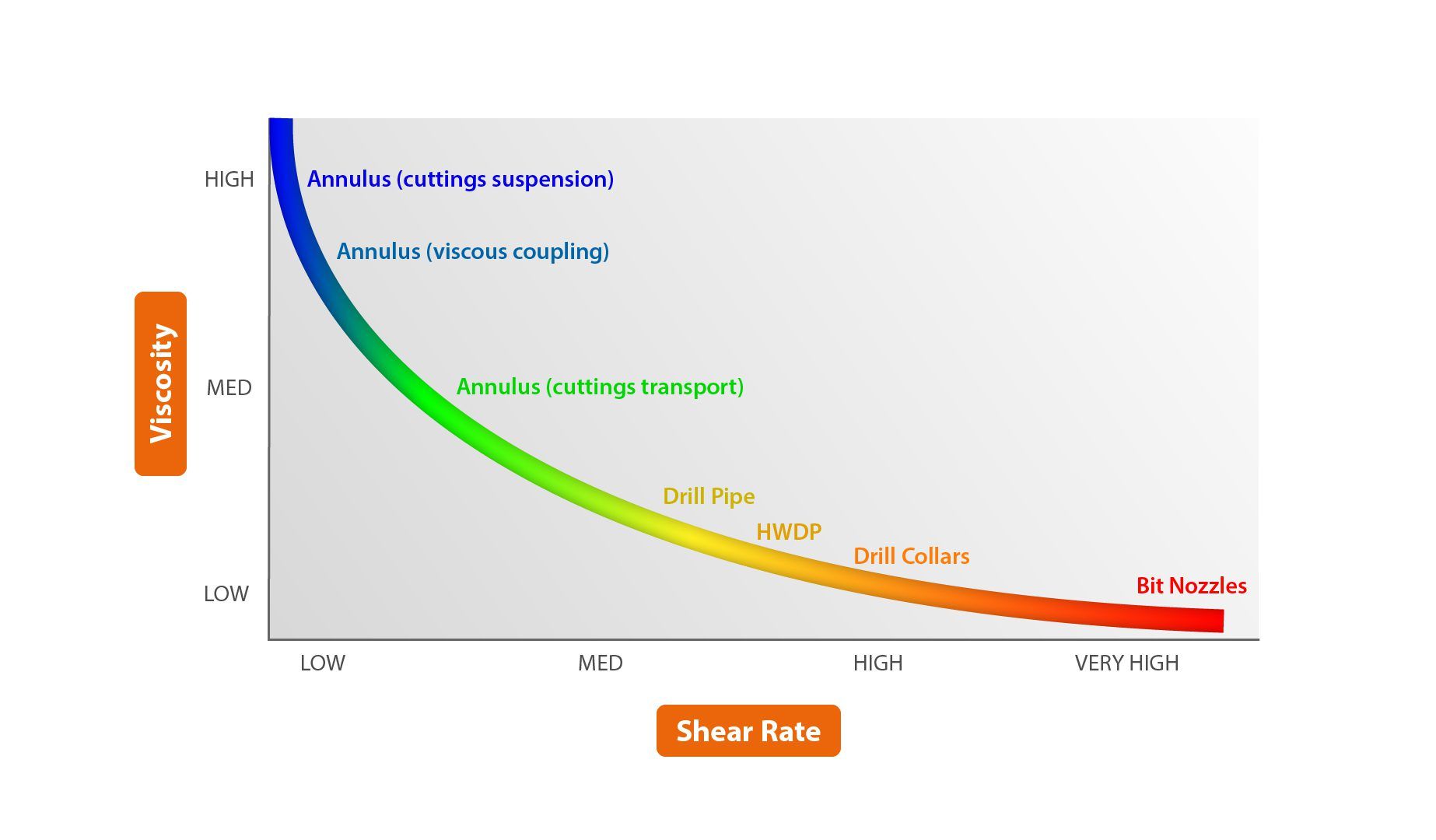

Understanding and being able to model the flow behaviour at different points of the circulating system is important.

- The shear rates inside the drill pipe, drill collars and BHA, are towards the higher end of the scale (see Figure 3) in the circulating system. This is where most of the pressure loss is produced and therefore has a major influence on circulating pressures and consequently the ability to deliver flow rates for hole cleaning.

- The shear rates in the annulus are at the other end of the scale, which is why the lower end rheology measurements are of more interest with respect to hole cleaning and ECD management.

The viscosity of the drilling fluid also has a major influence on other critical success factors for high angle wells:

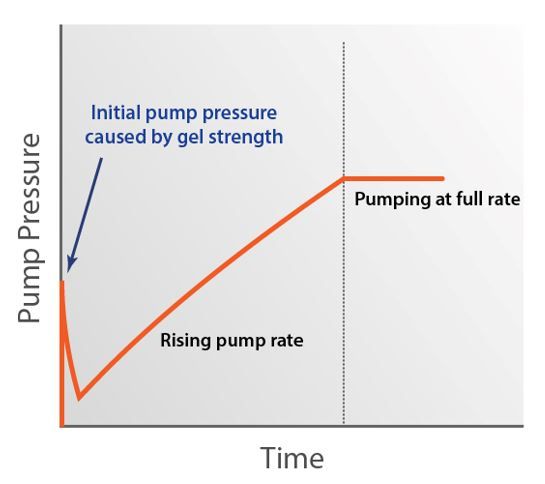

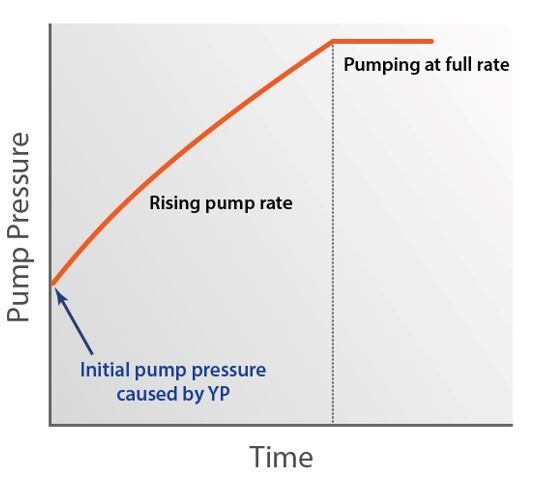

- The term “breaking circulation” is derived from breaking the gels to initiate flow in a well. The viscosity of the drilling fluid related to the gels is therefore important to reduce the risk of losses when bringing up the pumps.

- The viscosity of the drilling fluid has a major influence on swab and surge, which is clearly important in avoiding losses, instability, or an influx.

- Viscosity of the drilling fluid can also produce viscous drag of sufficient magnitude to limit the ability to run a light string in hole, for example a floated casing string.

- Inadequate viscosity is not only detrimental for solids carrying capacity, with respect to hole cleaning, but also with respect to suspending weighting material. Therefore, low viscosity fluids will be more prone to sag.

What is PV and YP?

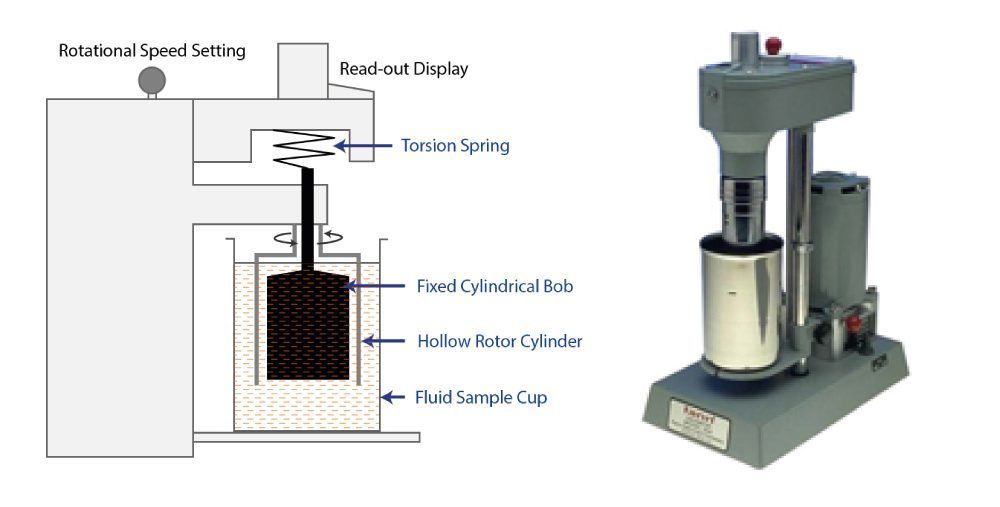

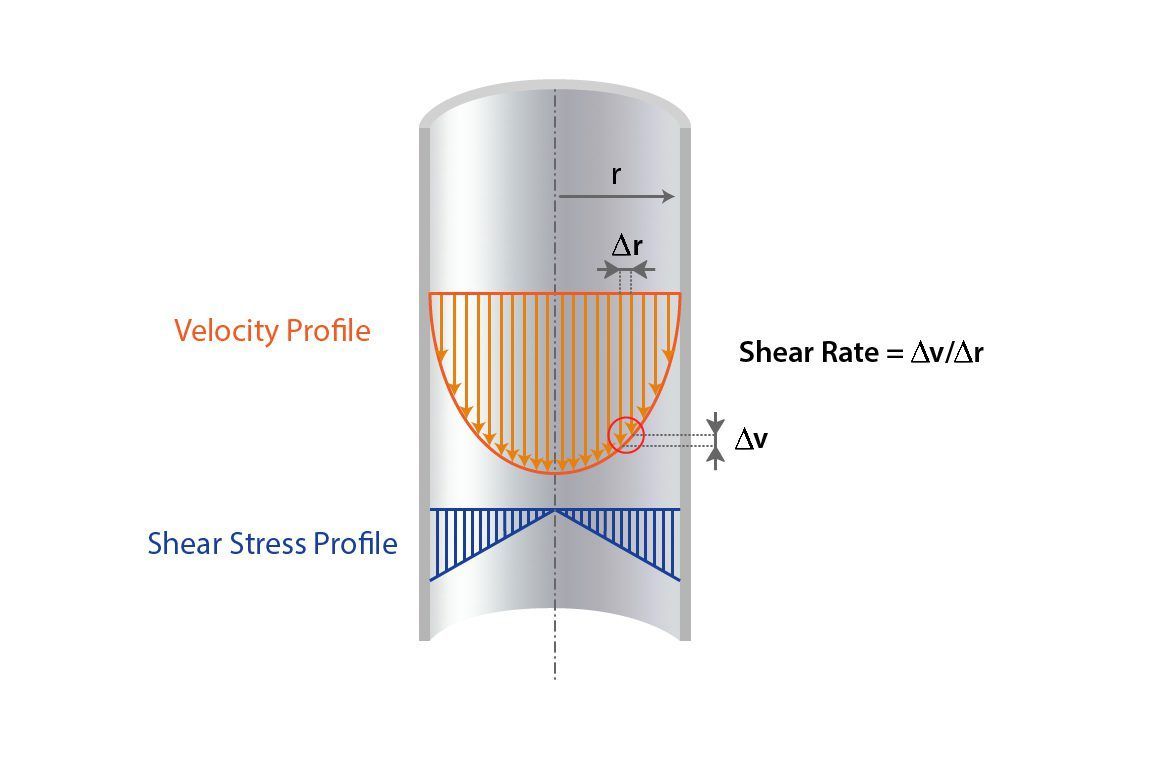

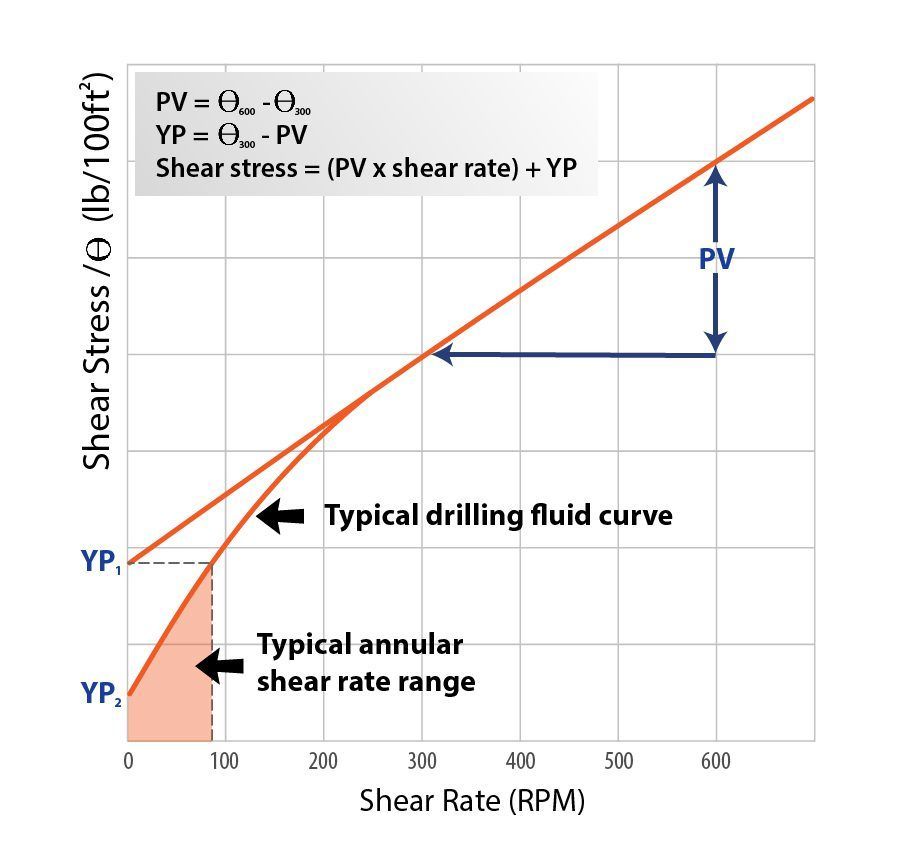

Plastic viscosity (PV) and yield point (YP) are two coefficients used to monitor the non-Newtonian properties of drilling fluid. There are many different models and manufacturers of viscometers, however they all share the same geometry and measure shear stress at the standard six speed (RPM) settings. The difference between the dial readings produced when the viscometer is set at the 600 and 300 RPM speeds is the PV and the PV subtracted from the 300 RPM dial reading is the YP. Historically, the higher end rheology readings (600 and 300) could be more accurately measured than the lower end readings, therefore the 600 and 300 RPM were used to define the Bingham Plastic straight line (see Figure 6 below). PV is calculated in centipoise (cps) and the YP is calculated in lb/100 sq ft, as shown below:

PV (cps) = ϴ

600

– ϴ

300

YP (lb/100 sq ft) = ϴ

300

– PV

Viscosities should be measured and reported at standard temperatures, which are usually 120°F for most wells or 150°F for high-temperatures wells. Typically six speed shear rates are taken at 600, 300, 200, 100, 6 and 3 RPM.

PV depends mainly on the concentration of solids and the viscosity of the base liquid and is more representative of the high shear rate viscosity inside the drill string. YP is a measure of the degree of non-Newtonian shear thinning behaviour (higher YP implies increased thickening at low shear rates). The YP is driven by the attractive forces between particles in the fluid at lower shear rates.

Is YP as measured by the mud engineer the actual YP?

No. Traditionally, rheology data has been used to calculate the YP and PV in the Bingham Plastic model (the straight line on chart below – Figure 6), which does not actually represent the shear rate / shear stress behaviour of most fluids. YP is supposed to represent the shear stress at zero shear rate (the y-intercept on the chart), so it should be lower than the 3 RPM reading. In reality, it is normally much high because the YP recorded in the mud report by the mud engineer is not actually the shear stress at zero shear rate, it is the y-intercept of the extrapolated straight line derived from the 300 and 600 dial readings (PV and YP). YP 1

shown on Figure 6 below is the value reported on the mud report and YP 2

is the actual yield point.