Pumping out of hole. Lubricating out of hole. Circulating out of hole. Four word phrases. Many interpretations. Potential consequences of the worst kind. We’re writing this guide in order to describe what’s going on downhole when circulating at the same time as pulling the drill string back to surface in highly deviated hole sections. Without throwing any statistics around, we often see companies engaging in high-risk behaviours when the pumps are on and the drill string is moving up the derrick. Our aim with this guide to is to explain in detail how our drill string (DS) and bottom hole assembly (BHA) interact with residual cuttings lying on the low side of the hole when tripping out of high angle wellbores; and how fluid travelling up the annulus at the same time interacts with both.

Let’s start by discussing some terms. The first term, which we’re all familiar with, is back-reaming. Back-reaming is defined as the process of drilling backwards. When we’re back-reaming, we are rotating the drill string and pumping drilling fluids at rates equivalent to those we are using to drill the hole section. The fundamental factors influencing hole cleaning (annular velocity (AV), drill pipe rotation and fluid rheology) are well known, so we won’t repeat them here but the key point is that efficient hole cleaning is achieved by getting the right combination of those three factors.

Another term which is often used to describe pumping while pulling is lubricating. You are unlikely to find two drillers who agree on the same definition of the verb “to lubricate”, so we will define it as “to circulate fluid through a work-string at a rate that is similar to the volume rate at which the string being pulled out of hole”. Let me know if you can do better than that! For our purposes, we will use “lubricate” to represent a situation whereby fluid is pumped at rates (and hence AV’s) much lower than would otherwise be conducive to ensuring the part of the hole cleaning machine sensitive to AV is working correctly.

When we are thinking about tripping out of hole, our first consideration – other than well control is ensuring that the hole is clean enough to trip out and trip something else back in hole, without encountering any significant problems. That means how we perform our clean up cycles should vary depending on the sensitivity of “something else” to cuttings beds. If we are simply running the same BHA in the hole again, then we will have a greater tolerance for debris left in the hole, compared to floating a casing string or running sand control screens with swell-packers. However, the point is that having the hole as clean as it needs to be will speed up our trip and mitigate risks on the next trip back to bottom.

Our clean up cycles are important here and related to the discussion around “lubrication”. As previously described, in high angle holes there needs to be some minimum combination of AV, drill string rotational speed and fluid rheology in use to get our drilled cuttings off the low side of the hole and on to the conveyor belt of high annular velocity fluid which will carry them, in a sequence of one to two stand hops, back to surface. Efficient hole cleaning reduces the height of the residual cuttings bed only as low as it needs to be before tripping.

With the section drilled and the clean-up cycles completed, we now turn our attention to the trip itself and the reasons why you might decide to pump out of hole or “lubricate”. Drilling is the business of managing risk by engineering and maintaining an adequate margin between loads and limits. On the trip, our geological limits are the minimum and maximum pressures that the surrounding rock can support before some kind of failure occurs. The loads that matter in this case are related to the pressure envelope we create when pulling out (swab) or running in (surge), with our pumps on or off. How surge and swab relate to the fracture and collapse envelope is a key consideration for any trip, with any string, in or out of hole.

Pumping out of hole can help manage swab issues, as described above. It may also help the string through a wellbore geometry feature such as a ledge, often in combination with string rotation. When we are considering the pump rate, what we really want to avoid is the “no-man’s land” between the flow rates we need to use to balance swab effects and rates which are effective for back reaming (which also must be done with high enough rotary speed). It’s not uncommon for us to see operators using flow rates higher than needed to manage swab but too low for effective hole cleaning (and without rotation). So what happens when we are pumping and pulling the string at no or low flow rates?

Firstly, without pumps. As we move the drill string up the hole, the entire drill string interacts with the entire column of drilling fluid. An effective fluid velocity is created in the annulus due to the fluid replacing the string being removed. The resulting pressure effect of this effective fluid velocity can be thought of in the same way as ECD (due to the speed of pipe movement and the rheological properties of the fluid), just in the opposite direction. This pressure therefore acts in opposition to the hydrostatic head of fluid in the annulus, reducing the equivalent fluid density (known as swab). Should the magnitude of that pressure drop below the collapse (or pore) pressure of the surrounding rock, we can induce compressive wellbore failure, or a well control incident.

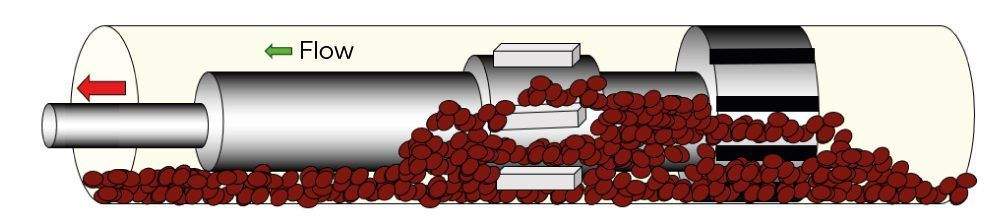

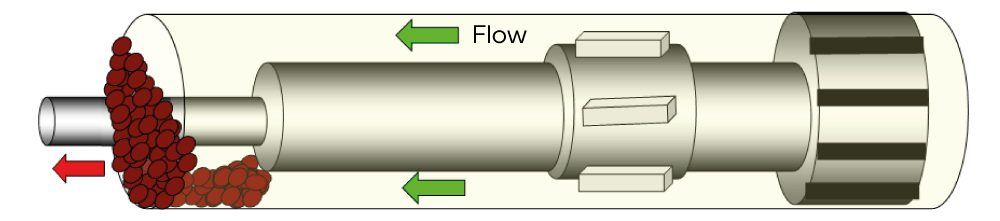

With the pumps on, we are cancelling out, or even reversing, the fluid flow in the annulus – to avoid reducing the annular pressure to below collapse or pore pressures. Modelling or rough calculations can tell us the flowrates we need to use in order to avoid swabbing at various tripping speeds and from these flow rates we can work out AVs around the BHA and drill string. Bear in mind that AVs by themselves will not generally be able to clean the hole around the drill string in realistic drilling conditions but higher AVs may be able to shift cuttings from around the BHA increasing the risk of pack-off, while not assisting in hole cleaning past the drill pipe. This may initially give the impression of clean hole, but over time as more and more cuttings build up above the BHA, the risk of permanently embedding the tools becomes greater.

What is it?

What is it not?

So, if we need to pump to balance swab or string displacement how do you de-risk it?

1. In the planning phase, if swab is identified as a risk, ensure that the risk is captured in an overall well specific risk assessment and that procedures are discussed in advance with the engineering and operations team to ensure that all are aware.

2. Make sure we are aware of our limits and loads – how fast can we pull at any given depth with the fluid properties we have in the well so we understand the conditions that will lead to swabbing or hole collapse (if this is a factor).

3. The hole should be as clean as it needs to be before starting the trip as we will not be cleaning it with the flow rates used to control swab or balance string displacement.

4. Minimise the flow rates in use. Higher flow rates increase AV which will clear more cuttings from around the BHA – meaning that the cuttings mound ahead will build up more quickly and in greater volume, meaning getting free is likely to be more of a challenge should we get stuck.

5. Have a road map for the trip, taking pick up data and using it to compare against the model. It is also important to select and impose overpull limits which are appropriate to the situation and that the team are going to stick to should divergence occur.

* See website for this to work: you can hover over each of the hotspots on the Merlin Methodology graphic below. Find out how we support this pumping out of hole in various stages of the project.

Recap

Lubricating or pumping out of hole can be managed safely provided that risks are identified and mitigated. Keeping AVs as low as possible, whilst managing swab or metal displacement is necessary to ensure that cuttings build up ahead of the BHA is minimised, which in turn minimises the chances of stuck pipe events in this part of the trip.