Companies vie to impress a skeptical Wall Street by eking out growth

Elite runners long chased the 4-minute mile. Major league sluggers competed for decades to beat Babe Ruth’s 60 home runs. For Dennis Degner, the next milestone is 25,000 feet.

Oil and gas wells stretched just a fraction of that length laterally underground in 2010, when the now-chief executive of

Range Resources joined the natural gas producer. Back then, innovations in horizontal drilling and fracking were just beginning to transform global energy markets.

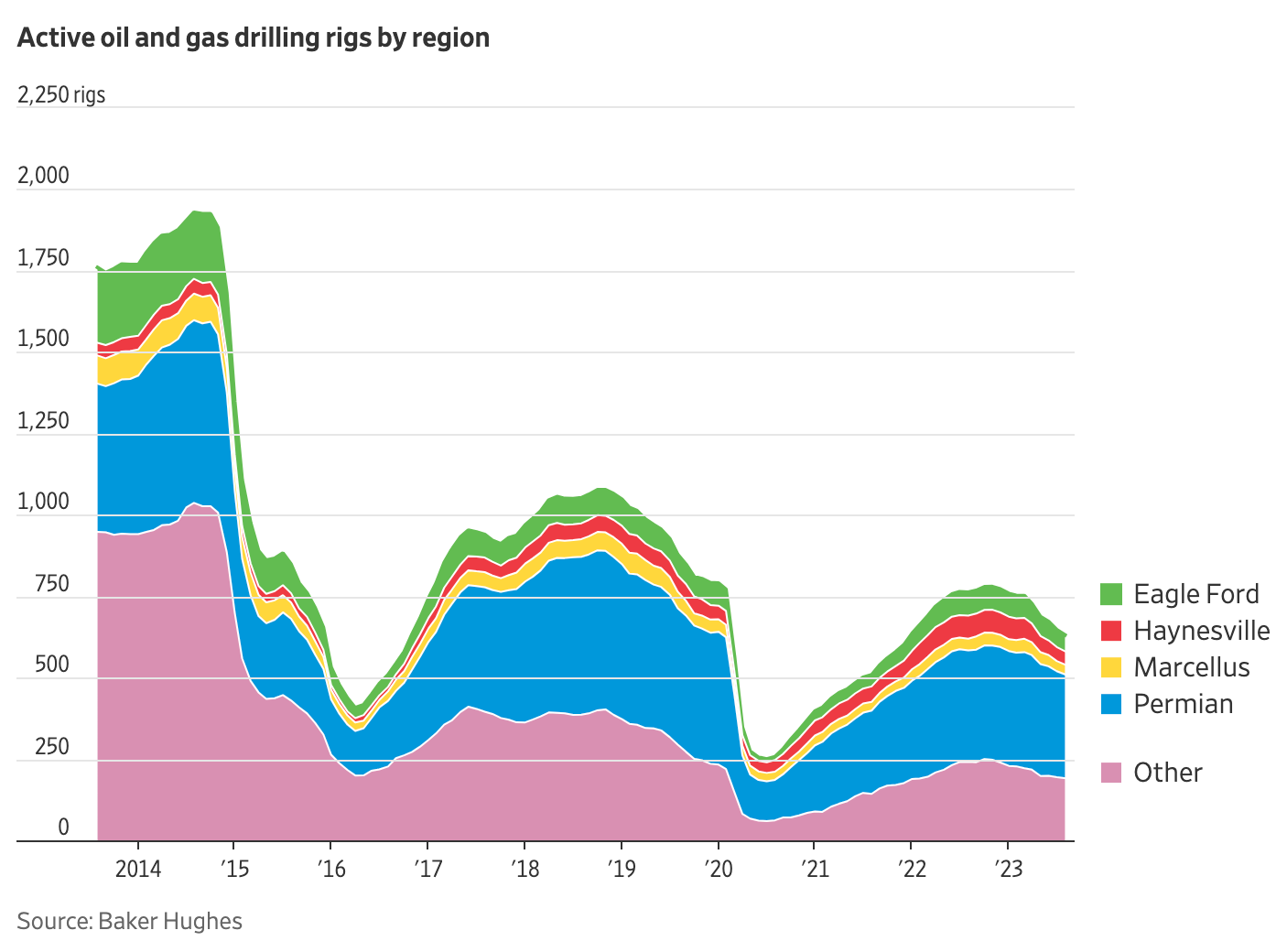

Now, with the end of the shale boom in sight, Wall Street is pressuring companies to cut spending and pony up returns to boost their share prices. Growth at all costs is out. The slow grind of achieving efficiency—alongside the office downgrades and recruiting struggles that come with it—is in.

Improvements that range from souped-up drilling rigs to specialized drill bits to technologies that provide better underground steering have helped firms recently pump out better-than-expected production—and dividends and buybacks for shareholders. The energy sector has been the S&P 500’s best performer over the past three months, outpacing even the information-technology and communications-services industries.

But some producers are boring so far underground with each lateral well that analysts say they are nearing the point of diminishing financial returns. In the long term, energy experts warn that the technological advance won’t be enough to reverse a structural decline in U.S. shale output in the coming years.

“How else can they show their investors that they’re getting better?” said Alexandre Ramos-Peon, head of shale research at Rystad Energy.

“We have probably reached the maximum we can do on a per-well basis,” he added. “Then it’s just a matter of being a volume game or waiting for the next technology breakthrough.”

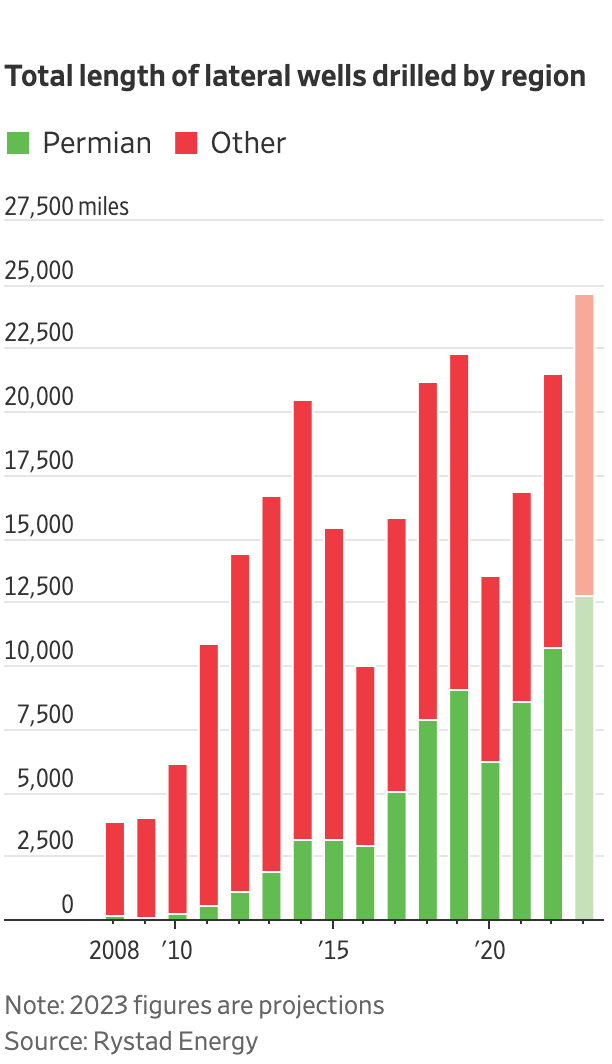

Horizontal wells drilled across U.S. shale basins this year will collectively stretch about 24,680 miles, Rystad projects, six times their 2008 total and nearly as long as the earth is round. The company said 16% of wells drilled this year in the oil-rich Permian basin, which spans West Texas and New Mexico, extended laterally beyond 12,500 feet. Only 1% did so five years ago.

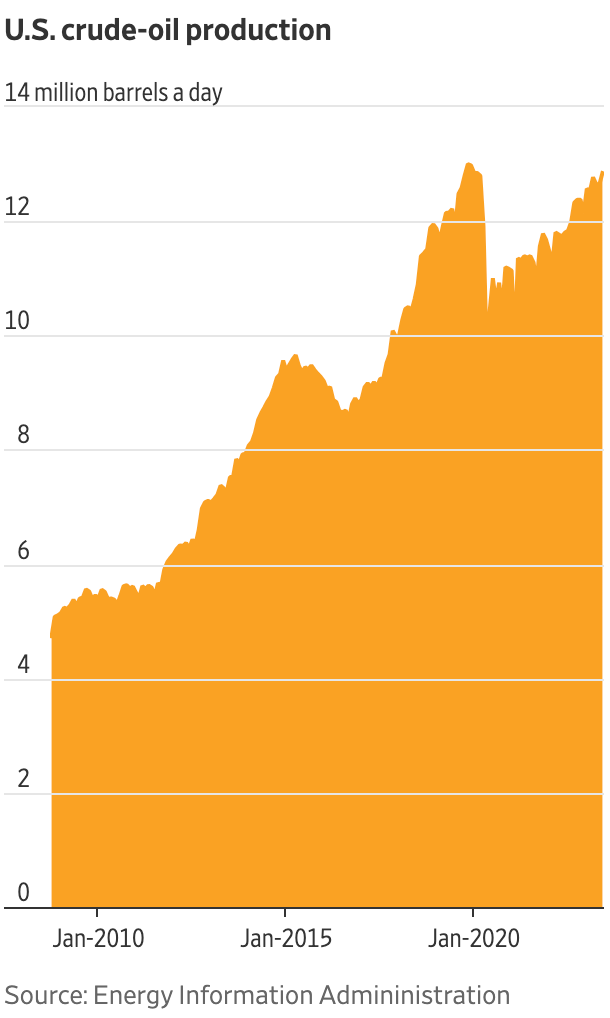

The gusher has blunted the impact of crude-production cuts in recent months by Saudi Arabia and Russia, weighing on prices at the pump. Front-month futures for West Texas Intermediate crude have traded at levels below traders’ projections for much of the year, only recently rallying to $87.51 a barrel.

Benchmark natural-gas futures have remained relatively stable this summer, trading Friday at $2.6050 per million British thermal units, even as Americans cranked up air conditioners in record-setting heat.

Boring farther to extract such supplies leads to more technical difficulties and geologic uncertainties, analysts say. Unexpected fractures in shale rock can destabilize operations and lead to costly equipment issues.

Companies have grown more sophisticated in mapping out such underground fault lines, said Alexandros Savvaidis, lead seismologist and manager of the Texas Seismological Network at the University of Texas at Austin. But it is likely they don’t know about all of them.

To avoid the minor earthquakes that Savvaidis and his colleagues have tied to shale activity in Texas in recent years, he added, “you try to avoid the faults that are sensitive.”

After longer wells are drilled, specialists such as Step Energy Services pump chemicals, water and sand into additional sections of shale rock, providing more chances for hydrocarbons to flow into the wellbore.

The Calgary-based oil-field-services company acts as a sort of plumber of the shale patch, snaking miles of coiled tubing into wells for tasks such as removing debris or helping flush out oil, sand and water. The reels of such piping have grown so big—14-feet wide by 16-feet tall—that 15-axle trailers take them to job sites, Chief Executive Steve Glanville said.

“You’re moving a house down the road,” he said.

Analysts say the longest laterals are concentrated among gas producers, rather than their oil-focused counterparts, in part because of the makeup of the prolific Marcellus formation that stretches across Appalachia. Outside Pittsburgh, Range Resources boasts a contiguous position of about 450,000 net acres.

That helped the company drill lateral wells of more than 14,800 feet on average last quarter, according to state regulatory data compiled by Stifel, greater than any other domestic gas producer.

“It’s a differentiator for us,” Degner said.

Written by David Uberti

View on the Wall Street Journal website